02

THESTORY

02

THESTORY

2019

-

2019

#1STEPISODE

THE OCEANS ARE DYING

MARINE SCIENTISTS FIGHT BACK

REEF RESTORER / NATHAN COOK

GODFATHER OF CORAL / CHARLIE VERON

MANTA WHISPERER / ABAM SIANIPARREAD STORY

-

2019

#2NDEPISODE

THE LAST EXPLORER

POLAR ADVENTURER / ERIC LARSEN

READ STORY

-

2019

#3RDEPISODE

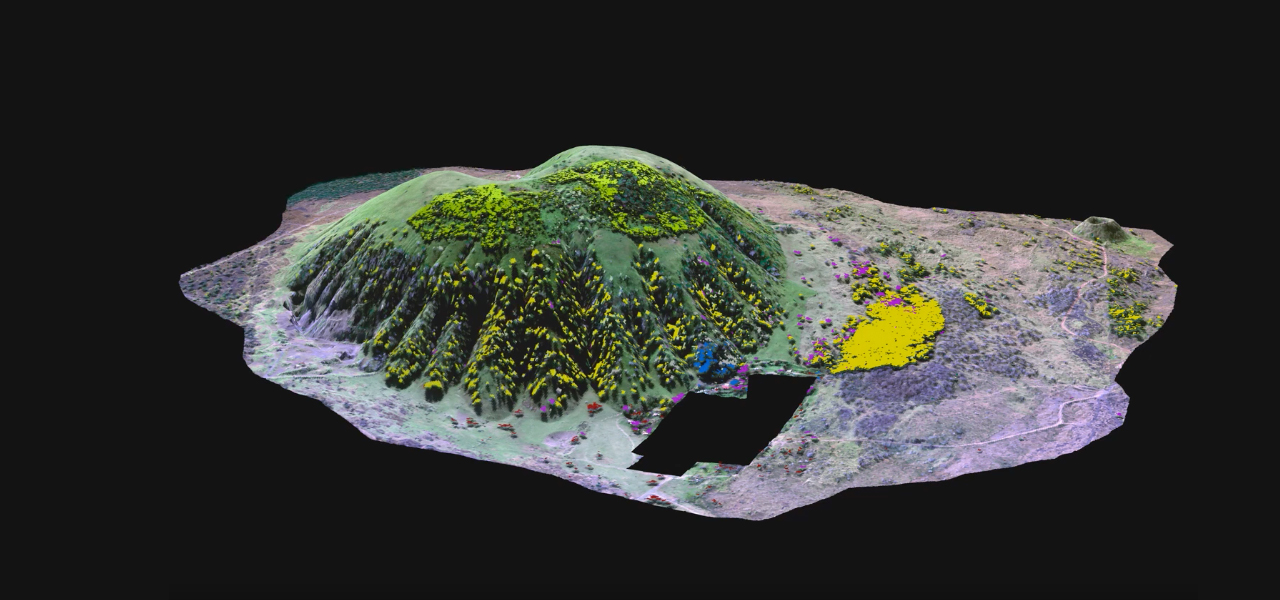

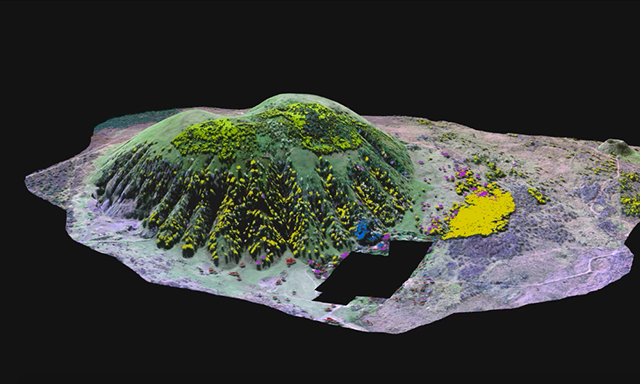

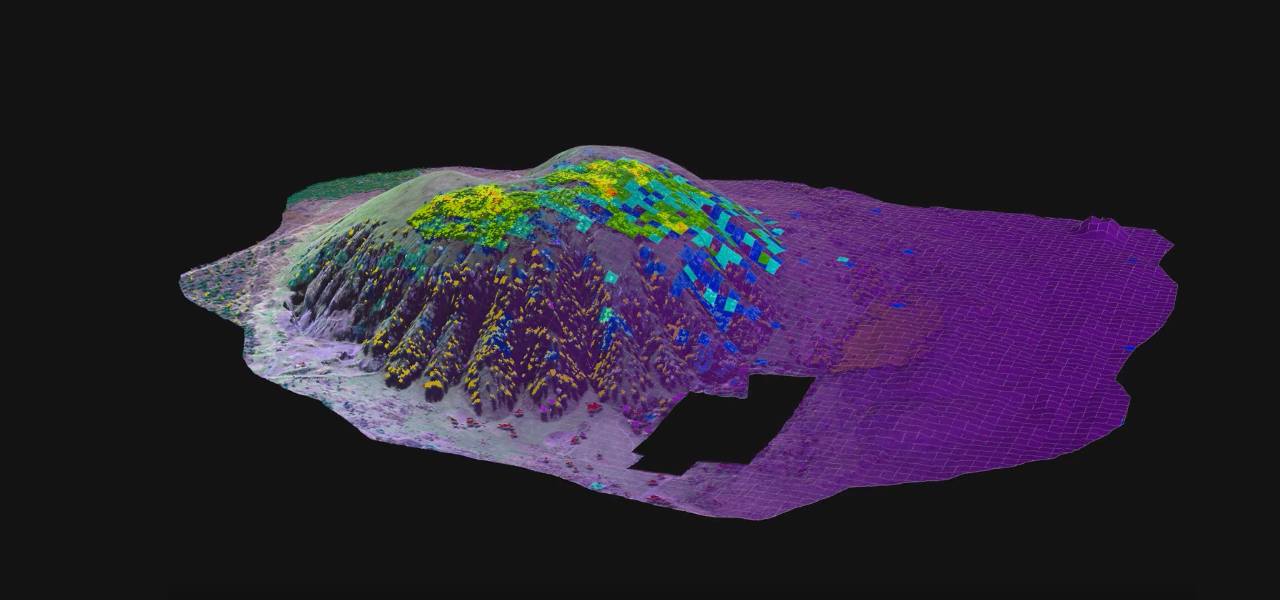

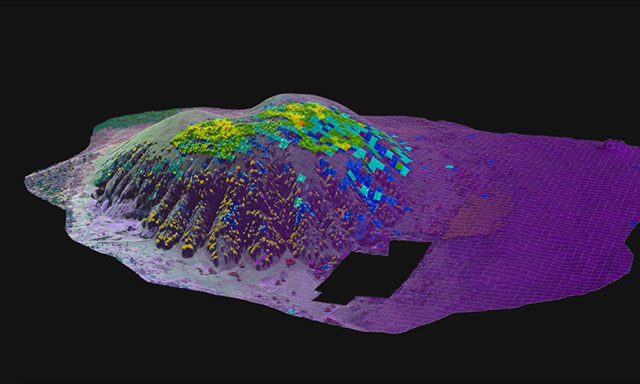

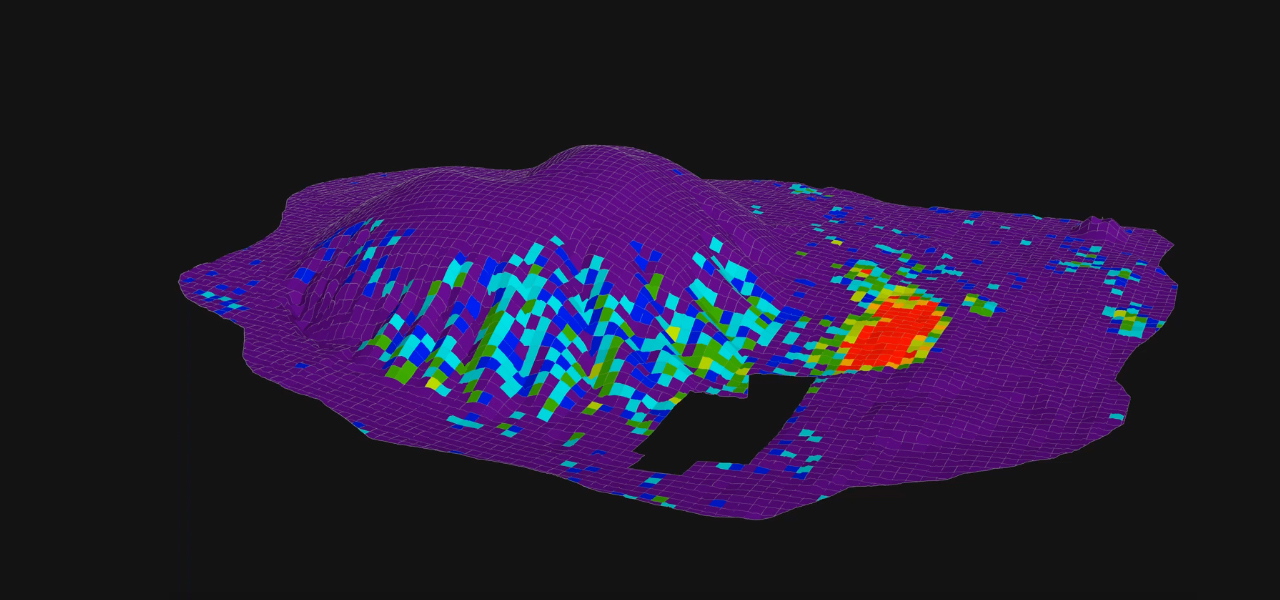

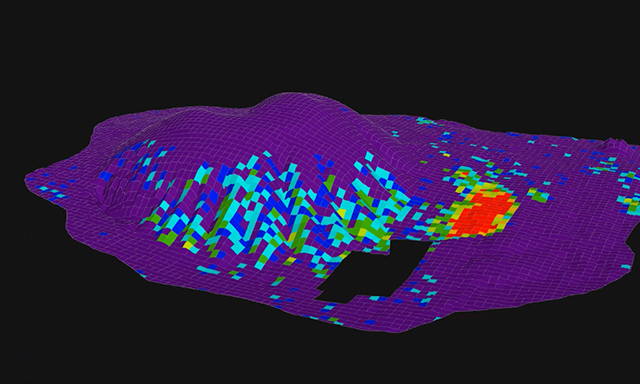

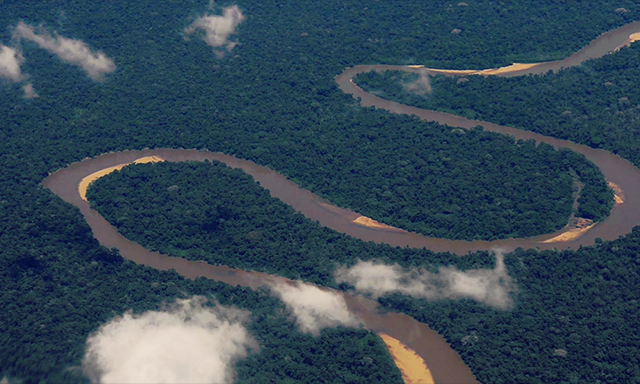

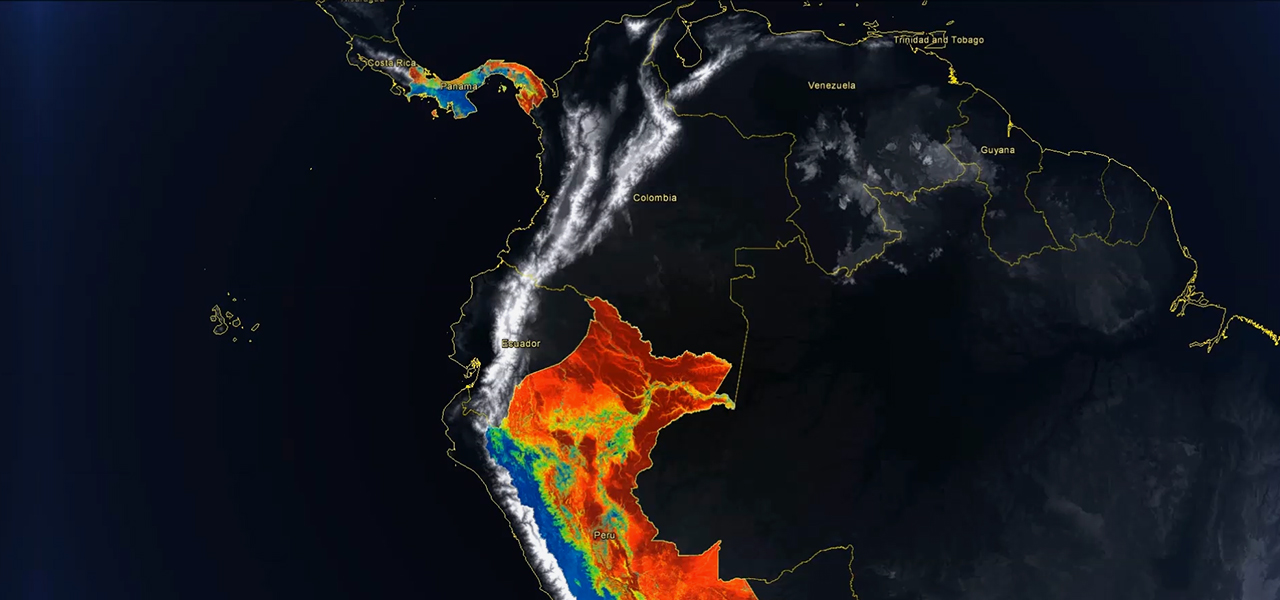

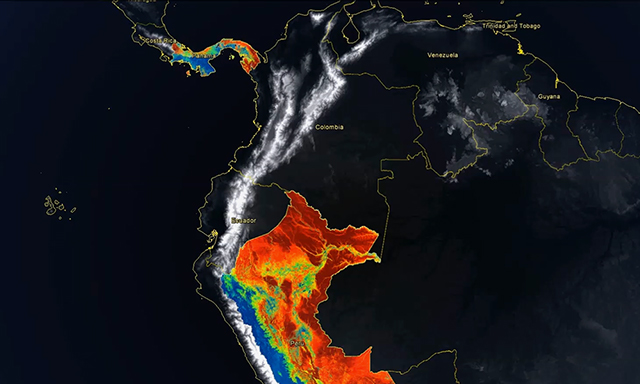

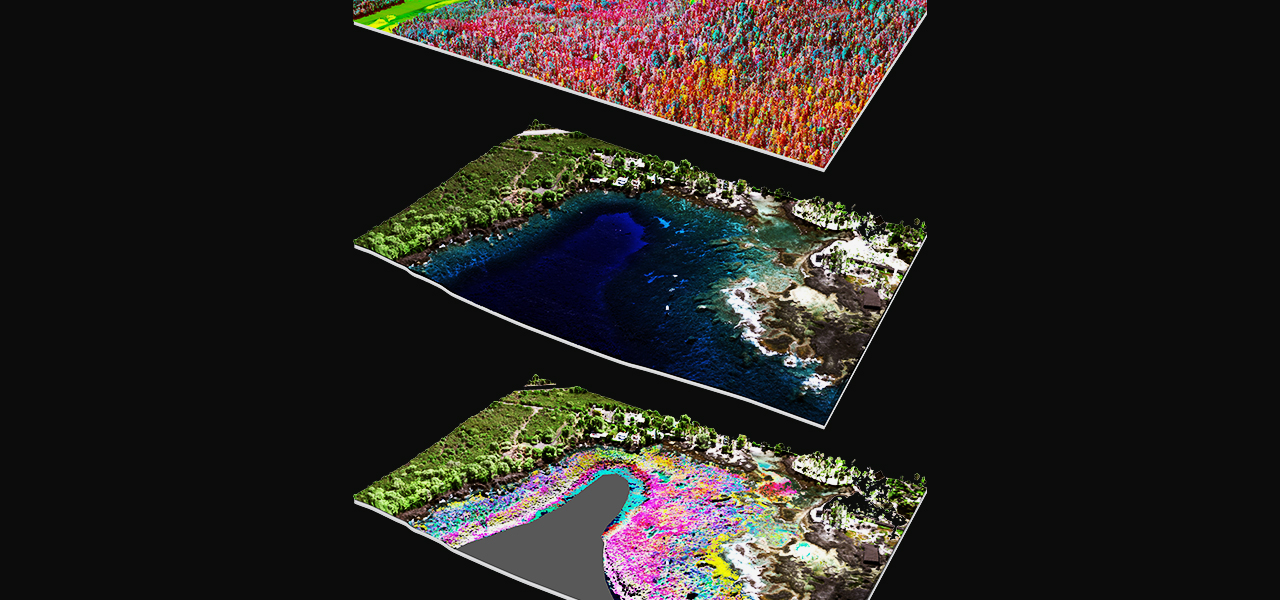

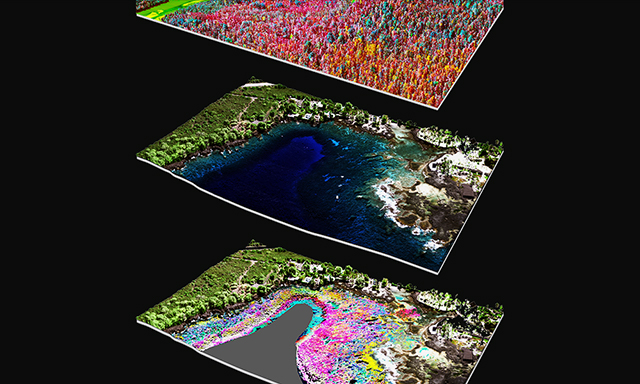

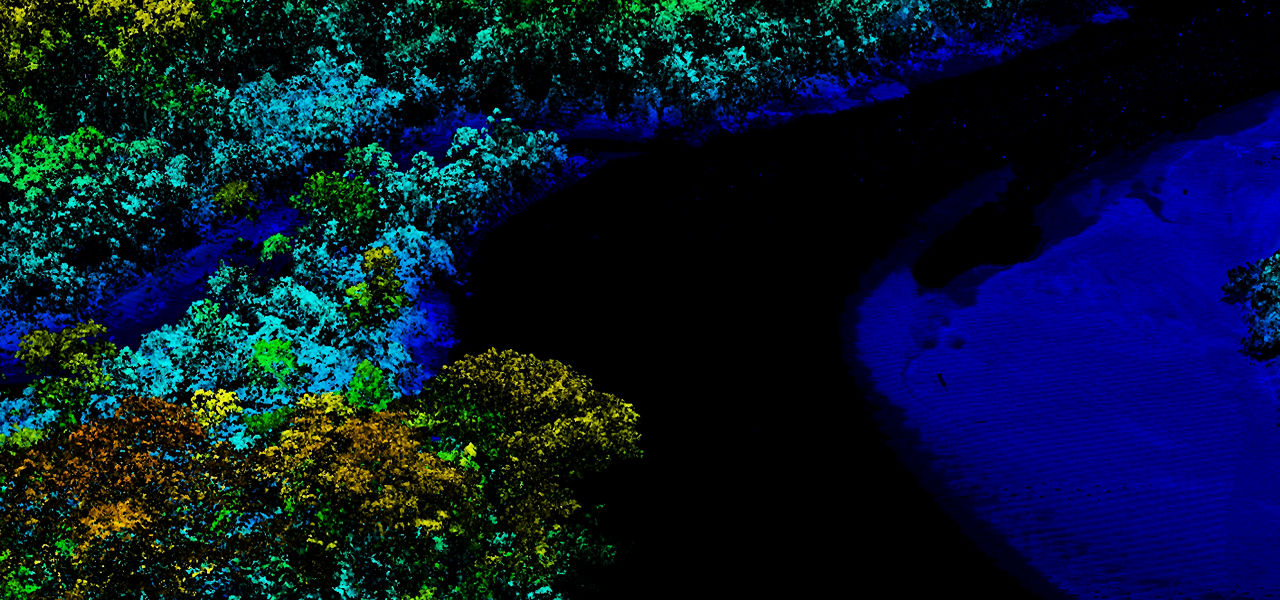

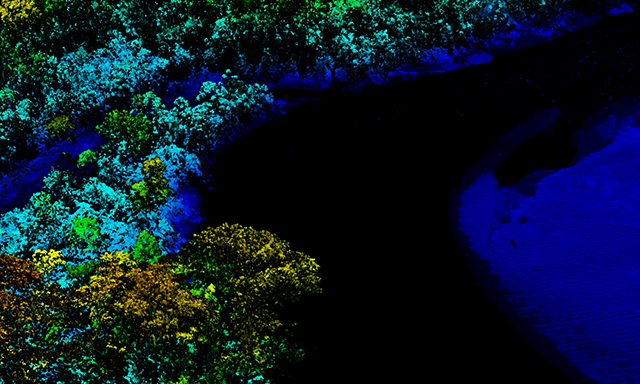

SAVING THE EARTH

FROM THE SKYECOLOGY TAKES TO THE AIR

AIRBORNE ECOLOGIST / GREG ASNER

READ STORY