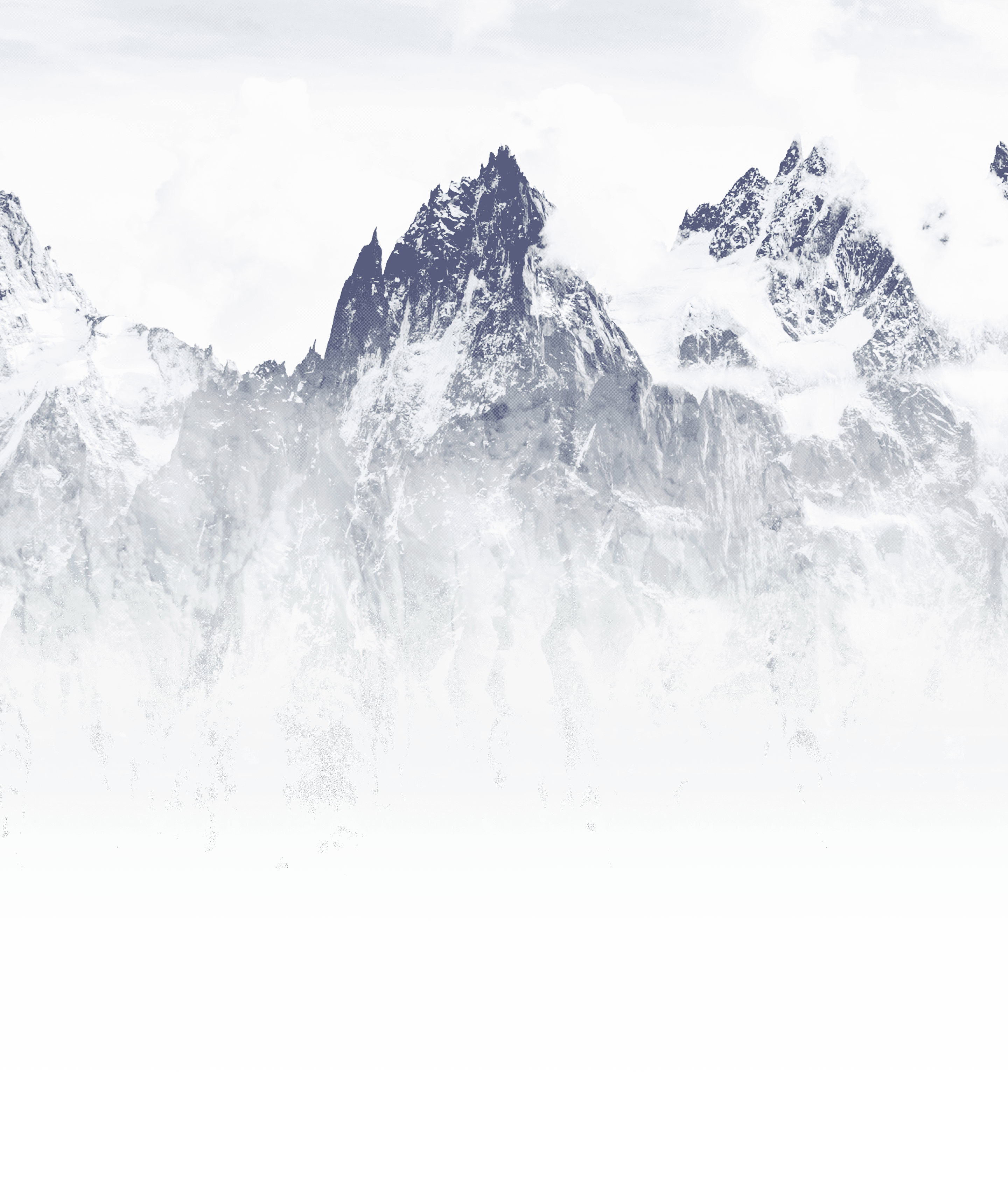

CLIMATE CHANGE INTHE BIRTHPLACEOF ALPINISM

Save the BEYOND A WORLD WITHOUT GLACIERS

THE MOVIE

(02)

“CHAMONIX IS THE PLACE WHERE ALPINISM STARTED.”

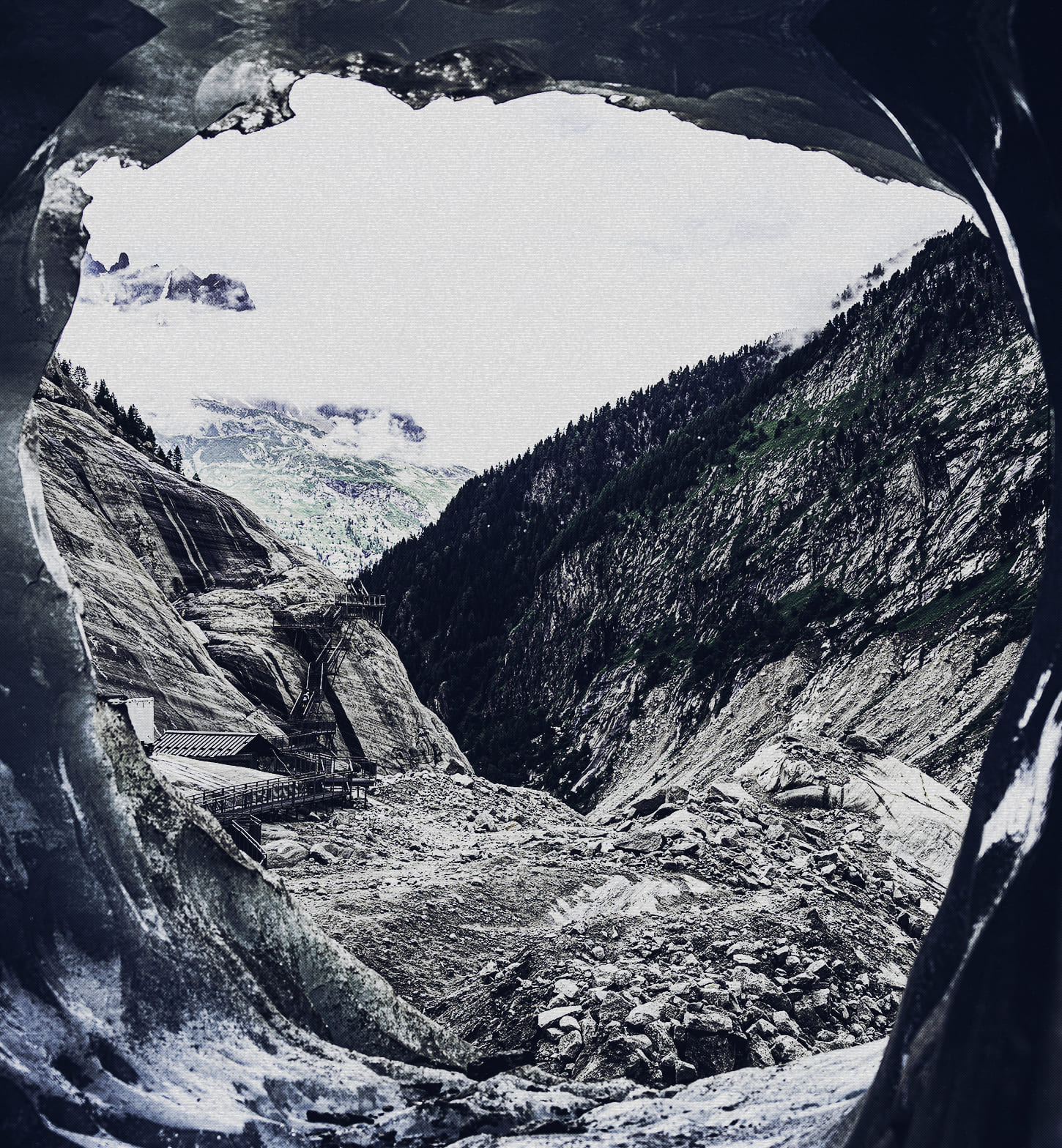

“IF YOU LOOK AT THE BOSSONS GLACIER, IT’S 400 TO 500 METRES HIGHER THAN WHEN I WAS A TEENAGER.”

“THE AMOUNT OF ICE WE’VE LOST IN THE LAST 30 TO 40 YEARS IS CRAZY.” “THE AMOUNT OF ICE WE’VE LOST IN THE LAST 30 TO 40 YEARS IS CRAZY.”

“OUR PLAYGROUND IS DISAPPEARING. IT’S FALLING APART.”

“I DON’T SEE GLOBAL WARMING AS THE END. WE CAN STILL ADAPT.” “I DON’T SEE GLOBAL WARMING AS THE END. WE CAN STILL ADAPT.”

THE LAST GLACIERSTHE LAST GLACIERSTHE LAST GLACIERSTHE LAST GLACIERS

THE LAST GLACIERSTHE LAST GLACIERSTHE LAST GLACIERSTHE LAST GLACIERS