Next Level Design

Truly one-of-a-kind brilliance, born of tradition and technology.

Sunago-maki Washi dial

URUSHI SAKAMOTO

Meet the craftsman who is creating truly one-of-a-kind watch dials by sprinkling Tosa washi paper with flakes of gold and silver —all while carefully maintaining the light-transmittance level Eco-Drive requires. Aizu-Wakamatsu in Fukushima Prefecture is famous as the home of the 400-hundred-year-plus tradition of Aizu lacquerware. We spoke to Asao Sakamoto, the third-generation head of URUSHI SAKAMOTO and a long-time CITIZEN collaborator.

Watch the movie

Creating new values by rethinking

urushi lacquer for the present day

Your company URUSHI SAKAMOTO is famous for applying urushi lacquer to modern-day industrial products. You’re the third generation of your family to head the firm, I believe?

That’s right. In Japanese, the company name is “Sakamoto Otozo.” It’s named after Otozo, the first-generation founder. He established the business back in 1900. Originally, we did lacquer refining—turning natural resin into something craftspeople could make practical use of. Ever since I took over the business in 1972, though, demand for lacquer has been in a downward spiral. Personally, I never thought it was enough for lacquerware to eke out a reduced existence as a material locked into one specific tradition. I’ve always been interested in manufacturing, and I had this idea of using urushi lacquer to make things in a way few other craftspeople were—namely, I wanted to add value to superior modern manufactured products through lacquer. That was the thinking that took us into the lacquering of products, which is the business we’re in today.

When you showed me around the workshop and gallery, I noticed a wide range of urushi lacquer-coated industrial products on display.

We’ve applied lacquer coatings to so many different products I can hardly remember what they all are! There’s watches and cameras, then there’s audio equipment like amps and speakers. We’ve even done fishing tackle, first-class seats in planes and interior panels for cars. Recently, we did the coating for the case of a heated tobacco product. We also make lacquerware accessories and gold lacquer bags under our in-house brand Sakamoto Collection.

When did you first do a collaboration with CITIZEN?

We’ve had an ongoing relationship with CITIZEN since 1991. It all started from a plan to produce some uniquely upscale watches. The one that stands out for me was a pocket watch designed especially for the use of women dressed in traditional Japanese kimonos. The watch was of 18-karat gold and the dial had a checkerboard pattern that was made by placing strips of gold leaf of different purity levels side by side. It sold out, despite being extremely expensive. Very memorable.

I notice that you’ve got a CITIZEN watch on today.

This is the 25th-anniversary model from The CITIZEN brand [out of stock]. I helped create it. It’s platinum leaf on washi paper. I wear it all the time. If you make things that you yourself want to buy, they’re sure to be a commercial success. At least, that’s how I see it. If you just do what you’re told, while secretly thinking in your heart of hearts “I’d never buy this thing myself,” then the product won’t be a hit. Whenever I make something, I try to make sure that it’s something I’d like to own, something I’d willingly pay money for. Anyway, one project led to another, and now the relationship with CITIZEN has lasted more than 30 years.

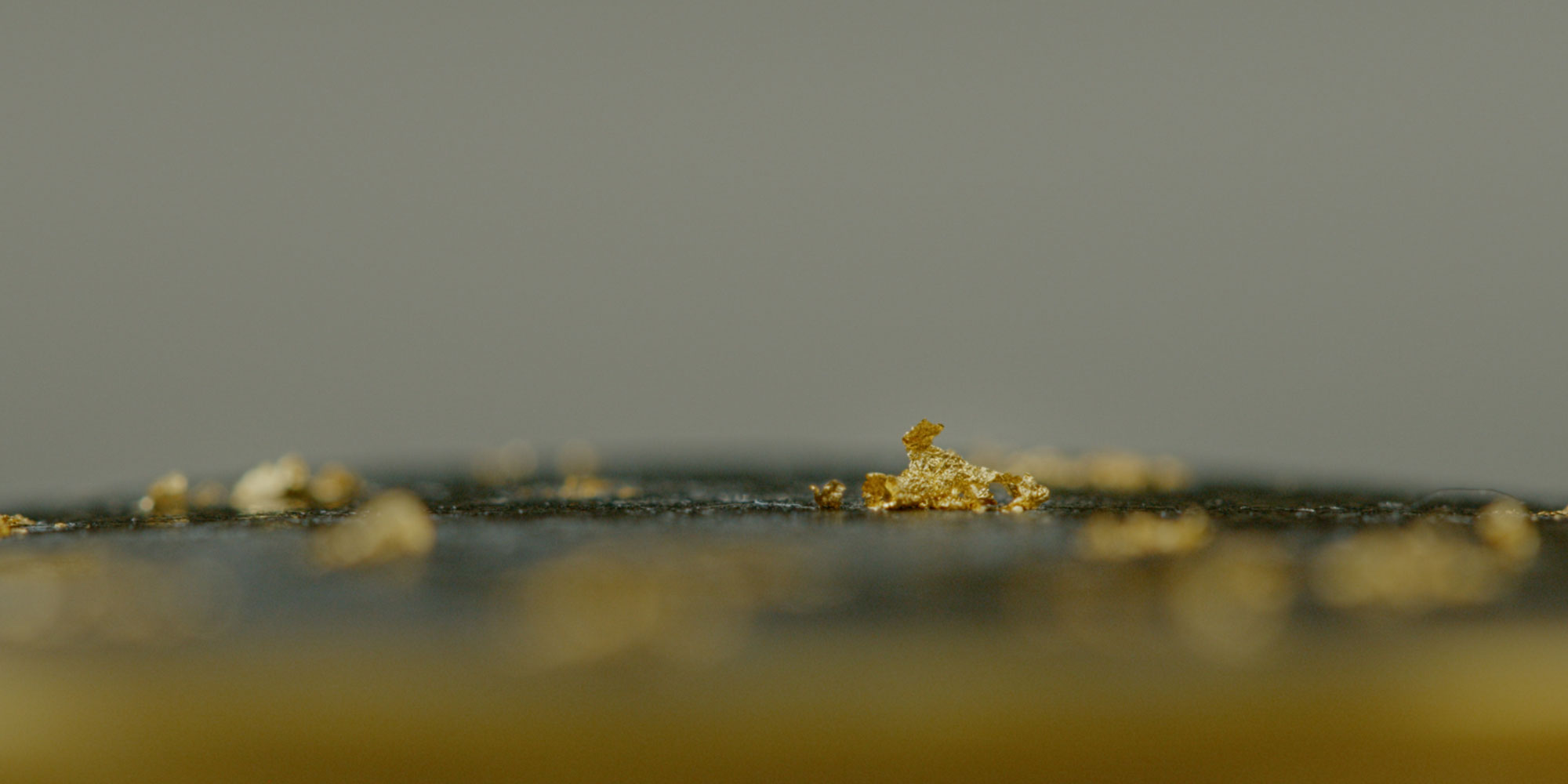

The image I had in mind was of gold ore from a goldmine.

I hear you used an old technique known as sunago-maki—literally “sand-sprinkling” in English—for the Black Tosa Washi Dial x Gold Leaf Model?

So we did. This particular project didn’t involve the use of any urushi lacquer, but I’m very used to using gold leaf. I’ve made a ton of products which I’ve decorated with gold leaf after lacquer coating them. That’s why I got the commission.

Sunago-maki [sand-sprinkling] is a pattern-making technique which involves sprinkling metal leaf onto washi paper. You shred the gold or silver leaf into little pieces which you then sprinkle about like snowflakes to create an effect like a sort of suspended haze. The image that sprang into my mind the minute I heard about the plan to combine gold leaf with a black washi dial was of gold ore. When you’re creating something, it’s crucial to have a single, clear image in the front of your mind. I knew that if I could create a finish evocative of gold ore with speckles of gold dotted about on black, the dial would have a sense of depth and be amazingly beautiful too.

It never occurred to me that you placed the individual flakes of gold leaf on the dial one at a time. It’s incredible.

Using a brush to put each flake in position was the only way to create the gold ore look, with a random dotting of specks of gold. If you press down on the gold too hard with the brush, the flakes can end up buried in the washi paper. That’s what makes the combination of black washi paper and gold leaf a bit of a challenge. As a manufacturing company, CITIZEN makes all its products based on the strictest quality control. Even so, the feeling of flatness of dials isn’t something they can do that much about. So with this product, I saw my role as being to try to make the flat dial appear as three dimensional as possible.

You said just now that you use metal leaf a lot in your work. Do you have a way of using it that is unique to URUSHI SAKAMOTO?

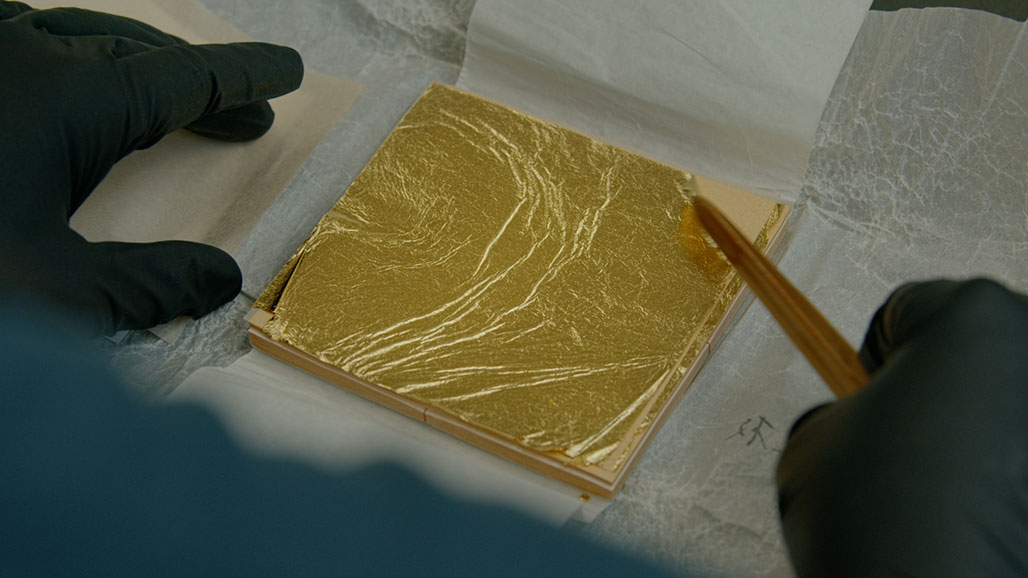

The standard approach with metal leaf is to stick it on flush with the surface. The skill is in just how smoothly and evenly you apply it. But what we do is to crumple up the metal leaf. Crumpling it produces the most beautiful folds and creases. It’s rather an extravagant way to use metal leaf, so I don’t think anyone else does it. It’s just us.

In my mind, irregularity is the definition of luxury. Modern industrial products are all about eliminating any irregularities or inefficiencies, right? The resulting products tend to be quite dull and boring. For us, the challenge—and it’s a fun, interesting challenge—is to create something irregular and interesting that can still pass all the manufacturer’s quality control tests. In this case, it’s the metal leaf that’s the irregular element.

Watching the production process, I couldn’t help noticing how carefully you pasted the glue on the dial.

You’ve got to coat the washi paper with glue to get the metal leaf to adhere to it—so far, so obvious—but it’s how you apply it that’s difficult. If you put glue near the centre and the metal foil sticks there, the dial can end up looking fussy and crowded. I take great care not to put any gold leaf near the dial’s centre because it looks bad when the hands [which are thicker there] overlap it. The same is true for the areas immediately round the indexes. You clearly picked up on how carefully I applied the glue, how I didn’t just slosh it over the whole surface.

You want to accentuate the gold leaf’s beauty

while letting as much light as possible through.

I was surprised to see you measuring the light permeability of every single dial you made.

It’s a big deal. The light-transmittance level is Eco-Drive’s lifeline because the technology works by converting light into energy. Obviously, if I sprinkled all the gold leaf onto the dial, not enough light would get through, so I didn’t do that. The light permeability of the black washi paper used for this model is not very good to start with, so if you then stick things all over the dial, it only makes it harder for light to get through. I measure the light transmittance of the individual dials to make sure there’ll be enough power for Eco-Drive to function. At the prototyping stage, I went through loads of dials to get a sense of what would work.

As well as the Black Tosa Washi Dial x Gold Leaf of Kanazawa Model, there’s a White Washi x Platinum Leaf Model. How is your image of the second model different from the first?

There’s much less of a colour contrast with platinum foil on white washi paper. It’s just silver and white. The more platinum you sprinkle onto the dial, the better it will look—as long as you maintain the necessary light-transmittance level, of course. “Wow, that’s luxury, that’s opulence!” is how people will respond. So I shook out a lot of platinum leaf like a shower of big, feathery snowflakes. The same technique wouldn’t work with black washi. The colour contrast would be too much, plus you wouldn’t be able to generate the necessary power. That’s the reason the thinking behind the gold ore concept of the black washi is completely different.

How did you feel when you saw the finished product for the first time?

Of course, I’d seen the washi dial before the indexes were added, but when the dial was fitted into the watch, I was struck by how the other decorative elements had really brought my image of gold ore powerfully to life. Another thing I really liked was the use of a domed sapphire crystal. That gave the washi paper dial even more three-dimensionality than I had hoped for.

I want people to see this watch as “a wearable piece of culture.”

When you’re creating a product, what do you regard as the most important thing?

People tend to think of traditional crafts in terms of a single material. That’s wrong. What you need to do is to use materials in a hybrid fashion. Take the washi paper and the gold leaf in this watch. You’ve got gold leaf made in Kanazawa, washi paper made in Tosa and maki-e, a decorative technique from Aizu lacquerware. They’re all fused together. That’s a really good thing. I don’t want the old ways of thinking—where one product was made in one specific place using one specific material and fired in one specific kiln. Japan has a vast number of top-class materials and craft skills, and we should use them all in combination. That’s the essence of the URUSHI SAKAMOTO philosophy.

The brand concept of The CITIZEN is about becoming a long-term and integral part of people’s lives. Are there any commonalties with URUSHI SAKAMOTO’s approach to monozukuri [making things]?

There are lots of traditional materials unique to Japan: lacquer, of course, but also the washi paper and gold leaf used for this watch, plus bamboo, I suppose. I want to use traditional materials and techniques to create value that transcends the whole issue of cost performance; I want to create things that people want to use forever. I call this “the life span of the attachment people feel for a product.” On this issue, our thinking is a match, no doubt about it. Combining URUSHI SAKAMOTO’s craft skills with CITIZEN’s core strengths of ultra-precise timekeeping and robust quality control generates a synergy effect that enables us to offer super-high levels of customer satisfaction.

Finally, what would your message be to people who have acquired This Sunago-maki Washi Dial Model decorated with gold or silver leaf?

I want them to think of their watch as a “wearable piece of traditional Japanese culture.” There aren’t many people out there who incorporating something traditional and Japan-made into their personal look. This idea of a wearable piece of Japanese culture links to what I was saying earlier about people feeling attached to products for the long term. I really want people to love this product.

About

The hand that makes the washi for the dial…

The hand that inspects the materials…

The hand that sketches the design…

The hand that assembles the watch…

Aspiring to be an integral part of your life.

In the pursuit of the next ideal in timekeeping,

The CITIZEN has a passion for making beautiful things.

The living embodiment of superior craftsmanship,

Our watches pass through a succession of skilled hands

Before reaching their ultimate destination:

the wrists of the wearers.

In Hand to Hand Story,

We highlight all the expert hands,

So dexterous, sensitive and thoughtful,

Required for the complex process of watchmaking.