The Craftsman’s

Perspective

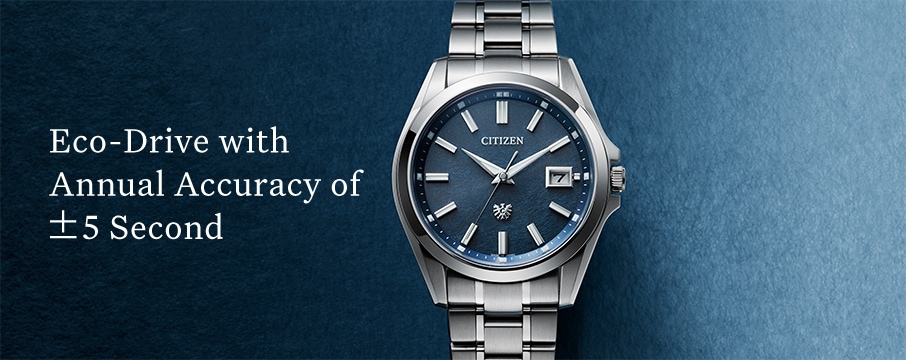

Eco-Drive with Annual Accuracy of

±1 Second and ±5 Seconds

Hand-dyed Indigo Washi Paper Dial Models

SCROLL

New possibilities from a washi paper dial

This is the first time CITIZEN has made hand-dyed indigo washi paper dials. There was a twofold challenge: dyeing the Tosa washi paper a beautiful indigo hue while also letting enough light through to the solar cell beneath the dial. Kenta Watanabe of Watanabe’s, a dye workshop in Tokushima, was in charge of half of that difficult mission. He discusses his experiences dyeing the washi paper and his feelings about his vocation.

It all starts with growing the indigo plants.

Everything I do is about creating one-of-a-kind colours.

What was your first reaction when CITIZEN approached you about indigo dyeing the washi paper for watch dials?

My first reaction when they got in touch was simply “What a great idea!” I knew instinctively that Tosa washi paper would make for gorgeous dials. I’ve dyed Tosa washi before so it’s a material I’m familiar with. The idea of combining its glossiness with indigo blue seemed like a match made in heaven. I was getting excited just trying to imagine what kind of watch CITIZEN would fit it into.

A watch is something you wear all the time, right up against your skin. Stop a moment and think about it, and you’ll realise that’s actually pretty unusual. It’s also quite a responsibility for me, so I was determined to dye every piece of paper with great care to achieve exactly the right colour.

Can you tell us about your first encounter with indigo dyeing?

It started when I was working in Tokyo. One day I got the chance to try my hand at indigo dyeing. The workshop where I did it used the traditional Japanese natural fermentation method, meaning they used a dye liquid known as a sukumo, which is made from the dried and fermented leaves of the indigo plant. It was all so exciting—the smell of the workshop, the way the dye oxidised and changed colour when you dipped your hand in, the gorgeous blue that would appear at the final rinsing stage. I was like, “I want to do this as a job.” So that’s the story of how I made my abrupt switch into this world. Previously I’d thought that strong colours meant vivid fluorescent yellows and oranges made with chemical dyes, but then I woke up to the appeal of this vivid and unique-looking blue. Natural colours have a lot of energy and indigo manages to be aggressive and gentle, all at the same time.

I believe that, as well as doing indigo dyeing, you also grow indigo plants?

At one point, I realised that you can’t create colours that are unique to you unless you start from tending the soil and growing the plants. That’s the basis of everything. Bottom line, indigo dyeing the way I practise it is really a branch of agriculture. I teamed up with a pig farmer who’s a friend of mine to turn fermented pig waste into the fertilizer which I spread on my fields. The local farmers respect the fact that I’m deliberately making a nutrient-rich manure that’s a good fit for the crops we grow around here.

So you’ve built a sustainable process in which natural materials are used at every stage?

If you’re firmly rooted in a specific place and you’re making indigo in a way that fits with the local environment then you’re making better use of the land, which leads to your making high-quality indigo in a more sustainable way. Everyone around here is committed to systems based on circularity and minimising food loss.

The fine line between light transmission and the perfect indigo colour

I heard that the Tosa washi paper used for the dial is extremely thin…

When I started, I thought I could plop the washi paper in the solution and dye it very cleanly and simply. In the end, though, washi is a different beast from fabric. The process of indigo dyeing involves dipping things in the dye liquid then rinsing them. Naturally, there’s a far greater risk of paper ripping than fabric. The solution I reached after a lot of experimentation was to strengthen the paper by applying a thin coat of natural starch made from devil’s tongue root. But you need to be careful. Use too much starch and you end up with lumps and colour inconsistencies. Finding the right balance was one of the tougher tasks I faced.

What sort of obstacles did you face in achieving the ideal indigo colour?

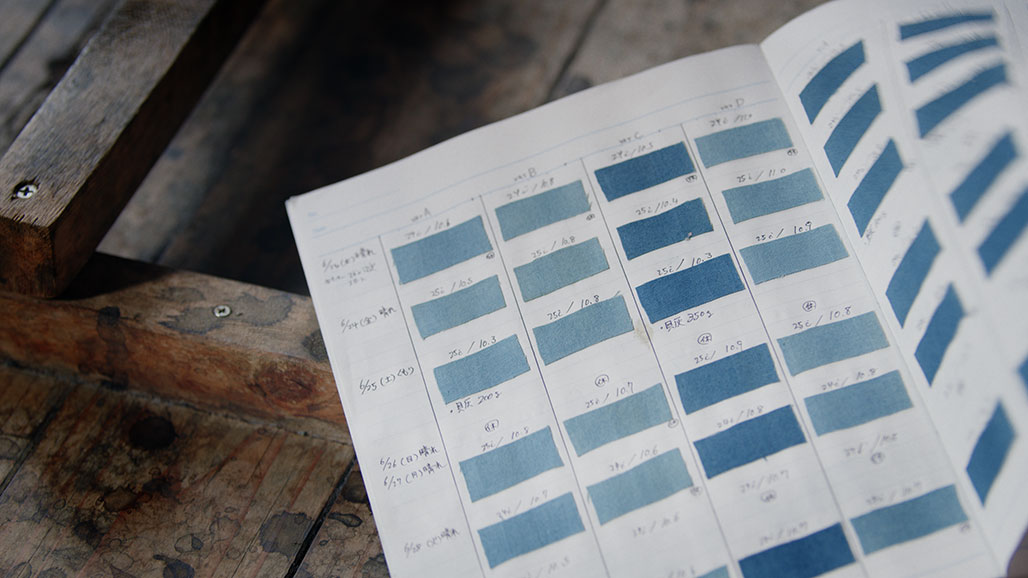

Because these watches use Eco-Drive [CITIZEN’s light-powered technology for driving watches], the paper dial needs to be light-permeable. The CITIZEN engineers and I had in-depth discussions and agreed on a target colour. When I did the dyeing, I was always aiming to achieve that colour. The thing is, though, that with the natural fermentation method we use in my workshop, the colour deepens through microorganic activity. Since the microorganisms are living things, the dye liquid changes from one day to the next.

Does that mean you can’t just follow the same steps every time?

Correct. Factors like temperature, humidity and the balance of the different raw materials affect the state of the dye liquid and subtly influence the fermentation process. As a result, simply dipping the washi paper the same number of times for the same number of minutes every time just doesn’t do the trick. It was a challenge and I put a lot of effort into keeping the dye liquid within a certain range of colour intensity.

There’s also the fact that indigo pigment only accounts for five per cent of the indigo leaf, with motley pigments other than indigo accounting for the other 95 per cent. With fabric, after you’ve dyed it, you can give it a good old rinsing and go through the process of washing out the motley colors. But because washi paper rips easily, you want to dye it the purest indigo you can, as quickly as you can…. The upshot is that I dipped the washi paper into the dye liquid three or so times to achieve the right colour intensity, but before that I did loads of experimentation to figure out how many times to dip it and for how long, and which colour was best for rinsing off all the non-indigo pigments.

Right: The washi paper is rinsed to get rid of colors other than indigo and then dried. The process is repeated several times.

Crafting objects that become a meaningful part of people’s lives

Did you enjoy the collaboration with Citizen?

I’m a master dyer and indigo is my specialty. Meanwhile, the job of The CITIZEN engineers is to figure out how to make the best watch they can. From the start, we agreed to have a free and frank exchange of opinions so that both sides could really give their best to the project. I’d be going to CITIZEN telling them, “I think this colour’s great” or “This colour reproduces very well.” Then they would come back to me with countersuggestions: “Can you manage something like this?"

I’m based in Tokushima [on the island of Shikoku], so we were creating the watch through a process of remote collaboration. Psychologically, though, there was no distance between us at all. The finished watch is a testimony to the quality of our communication. Our attitude wasn’t like, “This is all we’re capable of with the washi paper being so thin.” We had a very can-do spirit and were always trying to take things a step further. I feel privileged to have been part of a fabulous manufacturing process.

The concept of The CITIZEN is about “becoming an integral part of people’s lives.” Does that sync with your approach to making things?

Yes, it does. The merits of a product with a long life that can be used for a long time are self-evident. At the same time, a product is more than just a physical object. It’s the memories—the value that the individual brings—that turn an object into something truly unique. With the things I make, my aim is for them to develop an emotional resonance over time. In that respect, I’m pleased to say that my philosophy and CITIZEN’s philosophy dovetail quite nicely.

A final question. What would you say to people who are thinking of buying one of these watches?

For myself, I was blown away when I saw how nicely the indigo washi paper complemented the watch. It’s a gorgeous colour in the first place, but it looks even better when it’s fitted into the watch. I’d urge everyone to go out and handle the real thing—then buy one and make it an integral part of their lives!

A final comment from me. While the number of people who are aware of indigo as a colour is surprisingly high, the process for making it—the fact that the colour comes from plants or that the dye is made by fermentation—is barely known at all. The word indigo covers lots of dyeing methods and regional variations. I hope that this watch will make people aware of the complexity and fascination of indigo. People’s attachment to the watch will only get deeper if they’re thinking how great the Japanese art of indigo dyeing is whenever they strap it on.