Next Level Design

A thousand years of craft and legend come to life in a watch.

Tosa Seicho Dial

Osaki Paper

Light permeable while also allowing for beautiful colours, the Tosa washi used for the dial of The CITIZEN Eco-Drive is a unique material. It was first made 1,000 years ago and multiple varieties are now produced. One of them, Seicho paper, has been designated an Intangible National Treasure. There is only one craftsperson in all Japan who is heir to the traditions and techniques of making Seicho paper. Her name is Akari Kataoka and she’s the fourth-generation head of Osaki Paper, a family-run workshop based in the unspoiled landscape of Niyodogawa in Shikoku. We spoke to Akari about what makes her washi so special and her experience collaborating with CITIZEN.

Watch the movie

An endless round of hard physical work and mundane tasks.

Still, it’s worth it to keep the tradition alive.

Can you describe the Tosa Seicho washi you supplied to CITIZEN?

Tosa Seicho is a paper with long and strong fibres made 100% from kozo, a type of mulberry plant. We also make another variety of washi called Seikosen at our workshop. It has short, soft fibres and is 100% made from mitsumata, the oriental paper bush. But Tosa Seicho paper takes ink very well. That’s something that makes it very popular with calligraphers and printmakers.

I believe there aren’t many workshops left producing Tosa Seicho paper?

That’s right. As I understand it, nearly all the families in this area were papermakers until the Meiji and Taisho periods [late 19th to early 20th century]. Now, though, we’re the only family left that’s still making Tosa Seicho paper with the traditional techniques, doing everything from cultivating the plants to preparing the ingredients and paper forming. I inherited the papermaking business established by my great-grandfather, so I’m the fourth generation.

When you showed me around the workshop, I noticed that your daughter was helping.

Yes, it seems that the whole family was working in the business even back in my great-grandfather’s day. Over time, a pattern developed, with the men handling the drying stage and the women taking care of making the paper sheets. Meanwhile, removing the impurities from the boiled bark was the job of the older members of the family. Basically, the whole family has to put their shoulder to the wheel for the business to be viable. My daughter now does the removing of the impurities; I did it when I was a kid myself, mostly for fun—and probably not very well!

What prompted you to take over the business?

Family lore has it that when I was a little girl, I made an announcement to the family: “I’m going to take over the business.” Papermaking is physically very demanding and involves the repetition of quite mundane and boring tasks. A large sheet of washi is 2 x 6 shaku [63 x 183cm]. Making a piece of paper that big is really challenging. Even as a child, I’d seen how hard my family had to work, so if anything, I was trying to keep my distance from the business, but I was inspired by the way that the paper we made was being sought out even by people from overseas. There was this time when I saw some really beautiful things made out of washi and I thought to myself, “I really can’t let these people down. Making paper is what I have to do!” It was probably only two or three years after I took over the firm that I fully committed.

Our skills are the least important thing.

Surrounded by nature, we harness nature’s power to make paper.

What’s special about the papermaking techniques you inherited from your ancestors?

Making our washi starts with cultivating the kozo mulberry plants, harvesting them, steaming them, and stripping off the bark by hand. We then boil the fibres in lime hydrate; that’s followed by tazarashi, or outdoor bleaching in the sun. Then comes the making of the paper sheets, which is again done by hand, and finally drying on wooden boards. We are committed to making everything ourselves, starting with the raw materials, and to making our washi in a natural context. No other papermakers stick to the traditional ways as much as we do.

One thing that struck me was how neatly the clean white bark from the debarked and boiled mulberry was arranged on the split-bamboo frame in the water.

That’s part of the tazarashi process. You rinse the bark in water to get rid of the alkaline solution, then expose it to sunlight to bleach it. You can use chlorine for bleaching, but chlorine damages the fibres, so you’ll get a longer-lasting paper if you use the power of the sun and its ultraviolet rays. That’s the secret to creating Tosa Seicho paper, which is nicknamed “thousand-year washi” because of its durability.

Something else that really impressed me was the sight of Hisanao [Akari’s husband] out on the mountainside using a straw brush to stick the individual sheets of paper onto big wooden boards to dry in the sun.

Once you have your paper sheets ready, the final stage—drying them on the boards and exposing them to sunlight—is key to making thousand-year washi. Sure, metal boards are more weather-resistant and take up less space, but with them, the paper dries too fast, and the fibres get damaged. Because the wooden boards and the washi are both made of plant matter, they stretch and contract in a similar way, meaning the fibres don’t get harmed. That’s another tradition that needs to be preserved. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not obsessive about sticking to tradition. Traditional methods are so demanding that we did experiment with easier methods. In the end, though, we found we just could not make the same quality of paper. That’s why we still use the old methods.

They liked the whole papermaking setting here.

I don’t imagine you get many requests to make washi for watch dials. Was the washi you made different from normal?

The people at CITIZEN were like, “Make it really thin for us, thinner than the paper you make for calligraphy. We don’t care if it rips.” We wanted to provide CITIZEN with the best washi possible; I’d have been happy to put years into perfecting my technique, but that simply wasn’t practical. Our paper can be a bit rough, because it contains other plant matter besides the kozo mulberry. Since I’d never made such a thin paper before, I didn’t know the right quantities of beaten fibre to put in, or how much water or tororo-aoi to use. [Tororo-aoi is the raw material from which neri is made. Neri is a suspending agent that helps spread the fibres evenly in water.] I was very much feeling my way. “Does this work?” “No? Then how about this?”

You were groping in the dark?

I guess I was. The thing is, the people from CITIZEN came all the way out here, halfway up a mountain and one-and-a-half hour’s drive from Kochi, to visit our workshop. I didn’t need to explain myself and we never had any disagreements. They opted to use our paper because they really understood it, they really got it. I was really happy about that. There are many kinds of Tosa washi out there. If they hadn’t come out here and seen the place, they might have gone with a different variety. I don’t think that making the paper as thin as possible was the be-all and end-all. I think that they went for this whole setting here. Preserving the traditional physical context of papermaking is part of the tradition too.

What did you think when you saw the watch with the Tosa Seicho paper dial?

To be honest, I was amazed at how good it looked. The paper we make is quite simple and natural. I wasn’t sure how well it would go with something glossy and shiny. But no, it was a perfect match. I was amazed at the beauty of the finished product.

Our paper has a unique surface texture called sume [a trace pattern left by the screen mesh used at the paper formation stage]. The pattern goes well with the watch. We don’t use thin strips of bamboo, which are supposed to be rot-resistant, for our screen meshes. We use stalks of Japanese pampas grass, an older method handed down through the family. It’s not like you don’t get any trace pattern with a bamboo screen, it’s just that it’s that much clearer and more visible with pampas grass.

* Japan-only model. Not for sale in other countries.

Passing the secrets of thousand-year washi on to future generations.

I heard that you have another big enthusiasm apart from making washi?

My nine-year-old daughter has already announced that she wants to succeed to the business after me. Taking over the skills and techniques is easy enough, but it’s a different story when it comes to the tools of our trade. I’ve used all sorts of tools over my career, but whether it’s the suketa [a frame and a mesh screen used in paper formation], the sickle or the special bark-peeling knife, you can’t make good washi unless you have good tools. I had this idea that it would be good if I could make my own equipment for myself, so I went off to study how to do it. That turned out to be really difficult and time-consuming. People always says to me, “Even if you can make the tools, surely it’s knowing how to use them that really counts?”

The mesh pattern of the suketa is wonderfully fine and delicate.

Yes, isn’t it? And there aren’t any craftspeople left now who can make the suketa used for papermaking. There are only two craftspeople in Japan capable of making the pampas grass mesh screen. My daughter wants to become a papermaker, so what I’m focused on right now, for her sake, is doing whatever it takes for me to absorb the tradition of the tools we use to make sure that papermaking know-how does not die out.

I want to make washi that lasts a long time and connects with the user.

The brand concept of The CITIZEN is about “becoming an integral part of people’s lives.” Does that tally with your approach to making things?

Absolutely. My grandpa [Shigeru Osaki, the second-generation head of the business who was awarded the Labor Minister’s Prize] always liked to say that while artists only live for a hundred years, their work lasts forever. As far as he was concerned, things that didn’t last were worthless and the whole point of the thousand-year washi we make is that it should last. It’s important for people to have good things that they can hold onto for a long time.

Was that the sort of thinking that inspired you to launch Kaji-House, the store associated with your workshop?

Definitely. I want everybody, children included, to know where they can buy washi and what kind of products it’s made into. We all like to dream, don’t we? Frankly, selling your product to a wholesaler who then sells it on and that’s that, all over and done with, is hardly the most inspiring business model. My encounters with wonderful works in washi and the artists who make them are what motivate me to make better paper. That’s why I set up Kaji-House. We sell the creations of international artists, book covers and letter sets, all made using our washi. I don’t want washi to be regarded as just something decorative; I want people to make practical use of it. I hope they will come to the shop, handle it and get a tactile sense of just how fabulous it is. We also run workshops where we teach everything—the raw materials, preparation, washi-making. I’m hoping I can contribute to the local community that way.

Last of all, what is your message to customers of the model with the Tosa Seicho paper dial?

The first thing I’d like them to do is to take a good look at the mesh pattern on the dial, something that’s unique to Tosa Seicho paper. With its nickname of “thousand-year washi,” Tosa Seicho is unusually durable, so I hope they will treasure the watch for many years and tell people outside Japan just how great it is. I’d like them to become ambassadors for the wonders of washi.

About

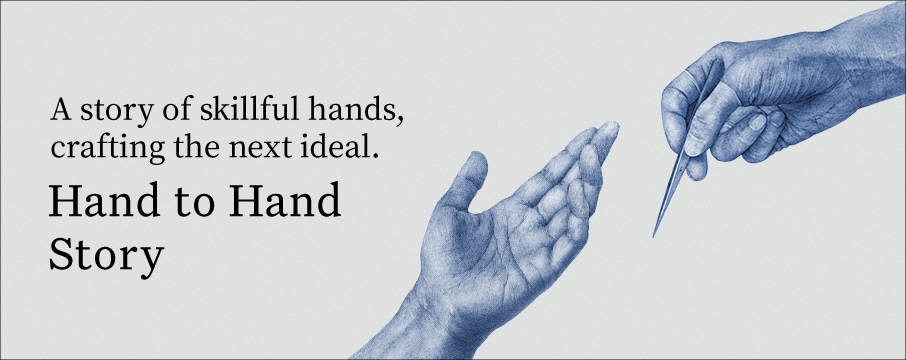

The hand that makes the washi for the dial…

The hand that inspects the materials…

The hand that sketches the design…

The hand that assembles the watch…

Aspiring to be an integral part of your life.

In the pursuit of the next ideal in timekeeping,

The CITIZEN has a passion for making beautiful things.

The living embodiment of superior craftsmanship,

Our watches pass through a succession of skilled hands

Before reaching their ultimate destination:

the wrists of the wearers.

In Hand to Hand Story,

We highlight all the expert hands,

So dexterous, sensitive and thoughtful,

Required for the complex process of watchmaking.